#interview, September 11, 2024

Content warning: this blog post may include unsettling images for some

Just before summer, Anya and Nathalie had the chance to attend the EASST/4S conference in Amsterdam—the 2024 quadrennial joint meeting of the European Association for the Study of Science and Technology (EASST) and the Society for Social Studies of Science (4S). The conference was a whirlwind of engaging discussions, with the concept of imaginaries woven through multiple panels. While we walked away with fresh ideas, intriguing perspectives, and a long reading list, the event again underscored how fluid and sweeping the concept of imagination truly is. Aligning with Matter of Imagination’s quest to dive into scholars’ diverse approaches to the realm of imagination, we talked to Gabriele de Seta during the conference to ask him about his ongoing work on algorithmic folklore and its ties to imagination.

Currently a researcher at the University of Bergen, Gabriele leads the ALGOFOLK project (“Algorithmic Folklore: The Mutual Shaping of Vernacular Creativity and Automation”). With a PhD from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, his research spans a fascinating intersection of folklore and the digital world. In our conversation, we dove deeper into Gabriele’s academic journey, exploring the many threads that connect his previous work to his current focus on folklore and the digital realm. Since we are both interested in imaginations from everyday culture, Gabriele’s focus on the vernacular was also the topic of discussion.

~ ~ ~

ANYA: We were talking yesterday about the number of buzzwords we hear now here, and STI (Sociotechnical Imaginaries) definitely is one of them. This is one of the reasons why we wanted to talk with you. When we think about approaches and concepts that help us talk about ideas and imagination related to internet history, who is there beyond Jasanoff and Kim? It is interesting for us to figure out how folklore fits into our broader mapping of approaches to imagination and imaginary. We wanted to talk about what you’re doing now and how it connects to the story of your academic interests. How did you go from writing about vernacular creativity on the web to now focusing on algorithmic folklore? What’s the connection between these terms?

GABRIELE: I read Olia Lialina and Dragan Espenschied’s book Digital Folklore in 2011 while finishing my master’s degree Asian Studies (on Chinese experimental music). It resonated deeply because it reflected my own ‘culture’. My friends and I, many of whom are internet creators from Italy, were all amazed by it—it felt like it represented our lives. I had been making websites as a kid and exchanging memes on early social media platforms like MySpace. This was the first book that made me realise that you could write about something as specific as weird fonts. Then, when applying to do a PhD in Hong Kong I thought: why not? Maybe I can work on the topic? Initially, I wanted to focus on Chinese digital folklore, but my supervisor was like, “no”. I was in a sociology department and everyone around me was telling me that “digital folklore” was not an academic concept.

The Digital Folklore book, published in 2009, is made available as PDF for free. Lialina writes: “One day there will be Digital Folklore 2 or Digital Folklore Reloaded, but in the meantime we release a PDF of the book (...). The original intention of digital folklore research and the book was to praise the amateurs who made computers and the web their own, and created rich vernacular cultures. Ten years later we still believe in user agency, in the power of peers to work, build, and exist outside of centralized services and walled gardens (...). So we put the pages of Digital Folklore into your hands, onto your computers”

Cover and page from The Digital Folklore book

ANYA: You essentially co-invented the concept later.

GABRIELE: I believe Olia and Dragan really coined the concept, and I tried to bring it over to the social sciences. I think there's a difference in my approach compared to theirs. Their focus is very much on GeoCities and the early vernacular web. That era involved a special kind of creativity—building your own website, learning to code, bottom-up creativity. My use of the term "digital folklore" is broader. I include memes from the 2010s and other forms of creative re-appropriation of technical tools. So, while I always relied on their definition, I also expanded it.

~

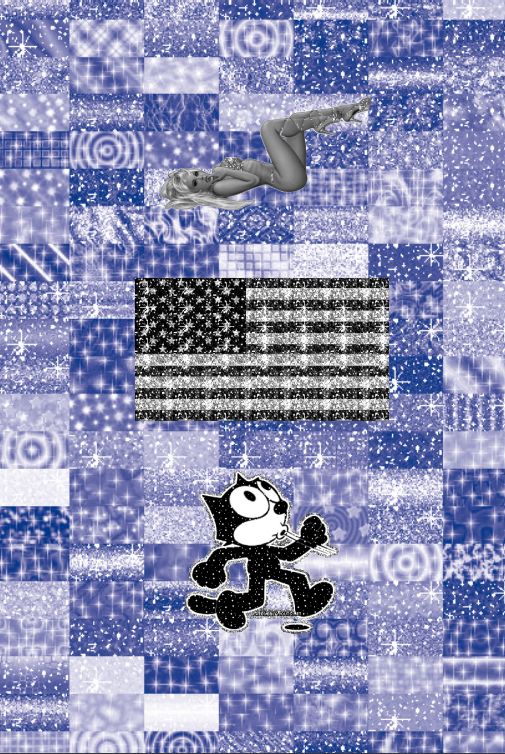

In the mid-90s, GeoCities emerged as a popular web-hosting platform that quickly became one of the most trafficked sites on the internet. Within a few years, there were 2.1 million members actively building their own “home on the web” through the platform’s novel free web-based services (...). GeoCities members could choose which neighborhoods they wanted to join based on their own interests and hobbies (MacKinnon, 2022, p. 237).

~

GABRIELE: During my PhD, I didn’t really use the term "digital folklore"; instead, I referred to it as "vernacular creativity," which is more aligned with Henry Jenkins and Jean Burgess’s work. But after finishing my PhD, I revisited the idea. I read extensively on folklore in anthropology, art history, cultural and media studies, and then I wrote a book chapter titled "Digital Folklore" in 2020. It’s essentially a comprehensive literature review of the concept and offers a definition that ties everything together. There are many histories of digital folklore.

"Folklore is a very old discipline, traditionally involving fieldwork like going to villages, recording songs, etc. But in the 1960s, scholars started recognizing folklore in cities, factories, television, and eventually, the internet.”

GABRIELE: There are books on folklore on the internet and the vernacular web, which are somewhat disconnected from what Olia was doing. Then, there's the anthropological perspective, where anthropologists study both folklore and the internet, using terms like "vernacular" and "prosaic" to describe creative practices. And of course, there's Henry Jenkins’s work on participatory culture and vernacular creativity and the artistic perspective that Olia and others used. In that chapter, I tried to find common ground and propose that we call it "digital folklore" across disciplines and also study it ethnographically. That’s the history up to this project. I’m happy with the work I’ve done on digital folklore, especially the definition and methods. I feel like I’ve said what I needed to say, and I’ve resolved the trauma from my PhD when I was told I couldn’t use the term. Now I’ve written a chapter about it, and hopefully others don’t have to experience the same trauma.

ANYA: You came to academia from the field you later decided to study, and now you're returning the knowledge you've gained to those who want to understand what they’re doing. It’s a very human approach to why doing research.

GABRIELE: Exactly. For me, that’s the whole point of writing.

ANYA: I want to delve a bit more into digital folklore. It seems like in your work, digital folklore isn’t just folklore that exists in digital environments. It’s also a tool for making sense of those environments. So, it’s not just about sharing anecdotes online but about sharing anecdotes that help make sense of the infrastructure itself.

GABRIELE: I think my main motivation has always been an interest in non-official, non-academic, and non-professional practices. Personally, I find these more fascinating—how systems are supposed to work versus what people actually do within them. Digital folklore, for me, is not just a funny meme shared on Facebook. It often reveals much about the media itself—who controls it, who governs it, how it’s structured.

NATHALIE: Is this where it connects with the concept of the imaginary?

GABRIELE: No, the imaginary is a newer interest for me. It didn’t really come up in my digital folklore work, but my new project blends these ideas - it is closer to algorithmic imaginaries, partly inspired by Tania Bucher’s work on the topic. Between those two projects, I worked on imaginaries as part of my work on the Chinese tech industry with the “Machine Vision in Everyday Life” project at the University of Bergen. Studying tech companies, especially in China, is challenging because you can’t easily do it ethnographically. Access to companies is limited, and COVID-19 made it even harder. So, it was a mix of circumstances that led me to this new focus.

~

Taina Bucher’s conceptualization of the algorithmic imaginary was discussed in her article on Facebook algorithms published in 2017. Here, she dives into people's personal experiences when scrolling on and interacting with the Facebook feed. Bucher’s definition: “[t]he algorithmic imaginary is not to be understood as a false belief or fetish of sorts but, rather, as the way in which people imagine, perceive and experience algorithms and what these imaginations make possible”(p. 31).

~

GABRIELE: The goal of this project was to understand how machine vision is imagined by these companies, but the challenge was figuring out how to study that. I read a lot of theoretical literature, which led me to concepts like sociotechnical imaginaries and imaginaries in general. The key question became: How does an industry, like the Chinese AI industry, represent its imagination of a technology? Who is the intended audience for this, and how can it be interpreted? What insights can we gain from these representations?

ANYA: The research we’ve done together previously also seems to connect to your interest in folklore, though I’m still thinking about how better to articulate that. Imagination and imaginaries are heavy concepts, and in our case, our interest in how machine vision is represented or imagined on websites didn’t quite fit under the socio-technical imaginaries framework, even though it was our initial approach. As we discussed methodologies and conceptual tools, we began to deal with more middle-range theories or concepts that captured what we were studying. That’s how we ended up describing these representations as visual registers or visual repertoires.

GABRIELE: Yes, exactly. That connection definitely comes from the folklore aspect, because terms like "register" and "repertoire" are used in linguistics, folklore, and anthropology. A repertoire usually refers to a collection of jokes, terms, or memes, while a register refers to a specific aesthetic or linguistic style. We just applied these concepts to web design.

NATHALIE: For us, it’s also very important to figure out how to discuss the vernacular level of imagination around technologies, imaginaries produced by everyday users. We also discussed the concept of lay discourses or lay imaginaries, playing around with that.

GABRIELE: This is where my new project, ALGOFOLK, comes in. To me, algorithmic folklore is an extension of digital folklore. In digital folklore, as a user, I might create something on platforms like Geocities or Facebook—like making websites or memes—which then circulates on the platform. But with algorithmic systems—such as recommender systems, generative AI, or chatbots—the process changes. The user can create something, and the algorithm can circulate it. Alternatively, the algorithm might generate something, like a music ranking or a chatbot reply, which the user then circulates. Sometimes, both the user and the algorithm collaborate in the creation and circulation process. I believe it represents a new kind of vernacular creativity—one that's not solely human or machine, but an interaction between both. A classic example of this is something like the ‘Crungus’.

NATHALIE: I've heard of that. Can you explain it?

GABRIELE: Crungus is a sort of monster. When DALL-E 2 became publicly available, someone prompted it with the word ‘Crungus’, which doesn't mean anything in any language. And yet, the model consistently generated an image of a monster resembling a troll or orc. No matter how you prompted it—say, "Crungus in Italy"—it always created this striking creature.

GABRIELE: The person who discovered this took it to Twitter, saying something like, "Oh my God, I found a monster hidden in AI; I'm scared; what's going on?" This led others to build on the story. In this case, the person just provided a word, and while it is humans who created a narrative, the machine generated the "folk" content itself, the visual representation. There's a loop where more people engage with the same algorithm, reinforcing the story around it, but it only works with that specific generative AI model.

"People have this drive to understand new technologies through concepts they already have, like legend, myths, horror. To me, this is a hundred percent folklore—it's absolutely fascinating.”

ANYA: It's partially determined by the algorithm or the website infrastructure, but not entirely. These systems influence people, who then shape them into narratives or stories. It’s fascinating to me that sense-making doesn’t just arise in a vacuum from our cognitive abilities; it’s always shaped both by media, but also by an interaction, by practice.

GABRIELE: Yeah, it’s social. And it's not just about generative AI—every kind of algorithmic system prompts these sorts of reactions. Even platforms like TikTok, which doesn’t create content per se, but curates the experience by sequencing what you see, inspire people to imagine the algorithm as something almost omniscient. This ties into the work of my colleague Marianne Gundersson. She explores how people feel that TikTok "knows" them—like discovering their gender identity or realizing they have anxiety because of the content TikTok suggests. It’s as if the algorithm is perceived as a godlike figure, knowing users better than they know themselves, better than their parents or therapists. At the same time, people also try to influence these systems. They watch certain types of videos to get more specific recommendations, or they create content designed to be favored by the algorithm. This constant interplay creates folklore around the algorithm, with people both imagining its power and trying to co-create with it.

~

Another example of algorithmic folklore is Loab, an eerie woman that kept reappearing in AI-generated images. The artist who discovered her, Steph Maj Swanson, says that she appeared after playing with negative prompt weights. This makes the AI create what it thinks is the opposite of the keywords entered. After the images gained virality online, the urban legend of Loab - the algorithmic folklore - was created; a woman is stuck in the AI model. “Is Loab some kind of presence within the system, whispers from the AI’s datasets given human form? Or is she just AI smoke and mirrors, born of our human desire to see patterns in the noise?”(Rose, 2022).

Tweet from @supercomposite

~

NATHALIE: I'm curious, is there a clear distinction between what you'd call an algorithmic imaginary and algorithmic folklore? Does it come down to the presence of a defined story or a specific artifact?

GABRIELE: Yes, I think there’s a difference. The algorithmic imaginary, as Taina Bucher discusses, refers more to the social space where people imagine what algorithms are and how they function. People draw on these imaginaries to create algorithmic folklore, so there’s definitely an overlap. Another related term in this area is folk theory. This refers to how people develop their own theories about algorithms without being computer scientists. For example, the TikTok case I mentioned and some of Taina’s work involve interviewing people about how they think the Facebook algorithm works. They might say, "I don’t know, but when I like something, I get more likes." That’s a folk theory. It’s not based on computer science, but it’s a way of understanding the system—and sometimes, they’re surprisingly accurate.

NATHALIE: Folk theory—that sounds interesting. Could you also say "folk imaginaries," or would that be redundant?

GABRIELE: There are countless papers and studies on various kinds of imaginaries. You can find concepts like corporate imaginaries, as well as governmental and socio-technical ones. So, there's no reason why we shouldn’t have ‘vernacular imaginaries’ as well.

ANYA: What I've been reflecting on throughout this conference, is how the term imaginary can be misleading. What we're really trying to understand is how ideas connect with practices or specific objects—how we make sense of technologies. It's more about how meaning-making happens. This ties into what philosophy might refer to as the field of imagination. But when we try to articulate precise concepts to grasp this, imaginaries might not always be the best terms.

GABRIELE: I agree. Imagination is the broad, overarching concept. In the imaginaries literature, the idea is that imagination isn’t just a side note—it’s crucial. It’s not just about reality, money, capitalism, or work; imagination plays a significant role in everything. The term imaginary helps organize this concept. An imaginary is like a structured or consistent form of collective imagination. For example, if I imagine something and you interview me, that’s my personal imagination. But if a thousand people share that same vision of a university, it becomes an imaginary—a shared, organized imagination about something.

ANYA: It is interesting how people develop similar structures or practices in folklore, it shows us that there are certain ways of thinking that are shared. The leap from individual to collective imagination is complex—how does my personal imagination become something shared? Is it because I'm learning from what powerful actors tell me, or from what I observe in everyday life? And what degree of agency do I have in this process? This is probably why many focus on corporate policy—it’s more obvious and easier to study.

NATHALIE: Is it driven by practices, or is it more about thinking? I've always seen it as a linear process, where practices are the result of imaginaries. But it’s clear they inform each other. In my project, I started by trying to understand the broader imaginaries of the early web. Then, I planned to conduct oral history interviews and dive into archives, which led me to focus on practices. But why not call those practices part of the imaginaries? Why not see them as a relay between imaginaries.

GABRIELE: Practice has been my obsession for about 10 years. I come from a social science and anthropology background, where culture is such a dominant concept. I’ve always disliked it and looked for an alternative. For me, the concept of practice is a way to avoid using the term culture entirely. I still try not to use culture because I think it doesn’t really mean anything concrete.

ANYA: That's a painful topic!

GABRIELE: I know! For me, all culture is essentially practice, and there’s some fascinating work in anthropology that supports this view. I might not write about it as much anymore, but it’s always at the core of my approach. When I study something, I focus on the practices of the people I’m observing—usually creative practices.

~

Exemplary work is written by Sherry Ortner in her book “Anthropology and Social Theory: Culture, Power, and the Acting Subject” (2008). She argues that culture is not a monolithic set of shared meanings or norms, but rather something that is constantly produced and reproduced through social practices. These practices are shaped by larger cultural frameworks, but individuals (the "acting subjects") also play a crucial role in how culture is enacted and transformed. Ortner’s work foregrounds human agency and - subjectivity and thus provides an interesting framework to vernacular creativity or everyday practices.

~

ANYA: You are recently experimenting with creative practice around your research topics yourself, right?

GABRIELE: I actually prefer that to the more high-level media theory stuff. I can do media theory, and sometimes I want to, but it’s intense for me—high commitment. When I engage in speculative or creative work, it feels on the same level as digital folklore. I’m doing the same thing, but instead of writing about it, I’m just doing it. In anthropology, there’s a strong tradition of experimental or speculative work, so it’s kind of natural. I try to do this kind of work regularly, especially things that might be shown in an exhibition.

ANYA: Do you see it as a different format for showcasing the results of your work, or is it part of the methodology that influences your main research?

GABRIELE: It’s definitely part of the methodology, and it can showcase results, but not in a direct way. I don’t like the typical data visualization approach. Instead, it’s more about showing things that you wouldn’t be able to capture in a traditional paper, but that you can express through creative work.

ANYA: You're a folklore knowledge activist!

GABRIELE: Yes, exactly. A good example of it is a Glorbo method of engaging with AI (here it is packed in a meme). The background of Glorbo is based on a real event. Someone on Reddit posted a thread saying: “Oh, finally, we’re getting Glorbo in World of Warcraft.” Now, ‘Glorbo’ doesn’t mean anything, it is similar to something like Crungus. But this person only made the post hoping that an AI system would pick it up. And sure enough, a videogaming news website published an article saying, “Glorbo finally introduced in World of Warcraft, and players are really happy.” This made it clear that this news website was entirely AI-generated, and it was scanning Reddit for content. I think Glorbo is a great example of what could be called “algorithmic folklore.” One person created it, it worked by chance, and then everyone talked about it.

Plant your own Glorbo

GABRIELE: You can visualize your own impact on AI. For instance, if you invent a word and start using it online, you can track how long it takes for something like ChatGPT to learn and understand it.

"This example of digital folklore shows that you can actually develop a method that anyone can use—not just to create more folklore, but to understand certain aspects of how AI works.”

NATHALIE: That makes sense. I wasn't sure about the difference between digital and algorithmic folklore before, but your example really clarifies that this interface—the interaction between human input and AI learning—is crucial.

GABRIELE: Yes, exactly. In the past, websites couldn't "learn" in this way. But now, with generative AI, we're seeing these boundaries become more apparent. AI is being trained on vast amounts of user-generated content, like Reddit posts, which makes it surprisingly easy to hack or influence. So, we’re likely to see more and more cases of this happening.

~ ~ ~

To cite this interview: de Seta, G., Fridzema, N., & Shchetvina, A. (2025, September 11). Algorithmic Folklore [interview with Gabriele de Seta]. Matter of Imagination. https://matterofimagination.neocities.org/blog4

Do you have any critique, response essay pitches, general comments, or (literature) suggestions after reading of this interview? Do not hesitate to get in touch with us!